My first introduction

to progressive rock was

likely Yes. But I didn’t know

it was prog rock because they

had hit songs and the complexity

went over my head, or I didn’t hear

it as complexity because I was not

yet a musician. As a pre-teen,

I started listening to Rush, but came

to them via their very first album,

pre-Peart, pre-prog, almost like a

Led Zeppelin cover band. And then

that second album with the new

drummer changed everything, but

I still didn’t really have a word for what

I was hearing.

The term “progressive rock” I probably

learned from the only private drum

instructor I ever studied with, a guy

named Sam Henry, a local celebrity

who played drums for punk bands,

The Wipers, The Rats, Napalm Beach.

He was a drummer technically way

over-skilled for punk rock, but he loved

the music, clearly, and was an intensely

powerful rock drummer. A key component

of his teaching style was to ask students

to listen to music with great drumming

and to play along to the records. As I was

learning to become a rock drummer,

I spent a lot of time drumming to my

favorites, and some time drumming to

music that Sam thought might be good

for me. The first time I ever heard

Emerson, Lake, and Palmer was in the

context of a drum lesson with Sam.

For whatever reason, I don’t think I liked

them. I never bought one of their albums

until, within the last decade, I came across

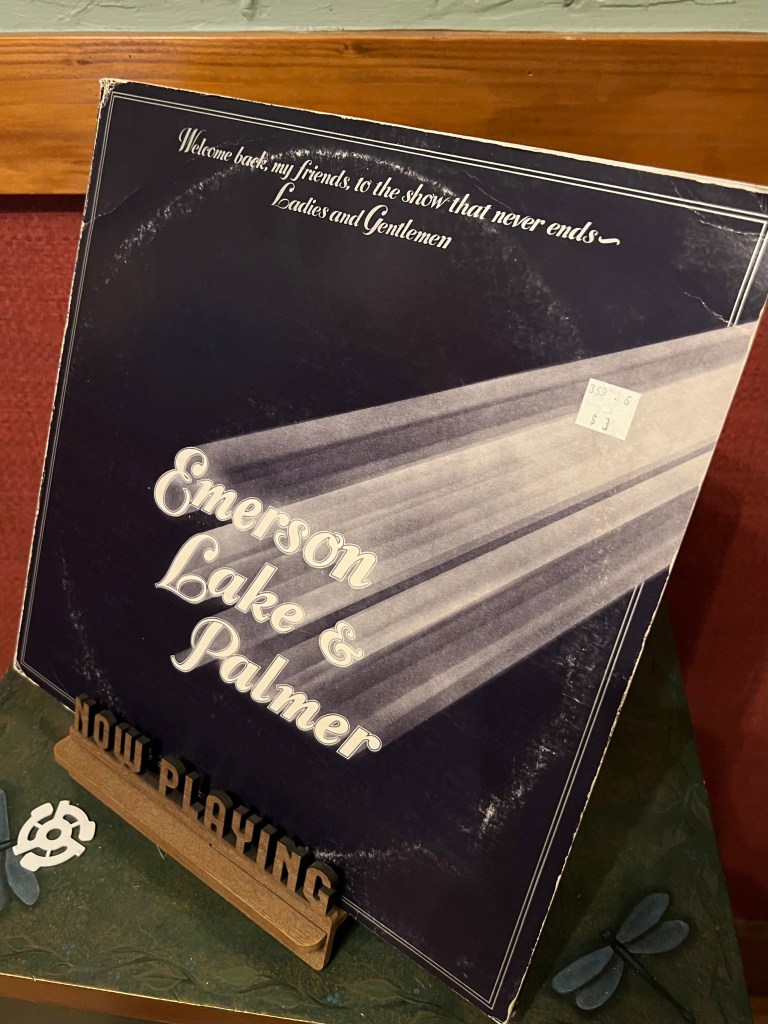

this three-album live set called Welcome

Back My Friends To The Show That Never

Ends–Ladies and Gentlemen, Emerson Lake

And Palmer. In part to pay respect for Sam Henry,

but also because I was curious and the

record was a steal at $3, I took it home.

I think I have listened to it maybe once,

but I can, from my earlier experience as

a youngster, accurately sing the title of

this album. Welcome back my friends to

the show that never ends. We’re so glad

you could attend. Come inside. Come inside.

Spinning side one. I mean, Kieth Emerson

must have been a kind of early genius

of rock and roll keyboards and synthesizers,

and I appreciate the historic nature of that,

but I just feel like I’m in some kind of

psychedelic skating rink in Great Britain.

A lot of crazy noise-making, rhythmically

complex ensemble movements, some

nice singing of absolutely ridiculous lyrics,

odd time signatures, crazy drumming,

but this is a shitty live recording from

1974 and I don’t find it very musical at all.

Outside of the skill-set prowess of these

three players, and Greg Lake’s seamless

switching from bass to guitar, I find nearly

nothing else redeeming about it, other than

it made me think about my teacher Sam Henry.

The question is: can I hang in there for six sides?

I don’t know that I can. I’m wearing headphones

to shield my partner from this nonsense,

but when I stand up to get a beer

and, so as not to miss anything altogether,

bump the amp volume through the speakers

just slightly, I find the music is much improved

at low volume from the stereo speakers.

Now the question becomes, can I stomach

six sides of this at low volume? I force

myself to keep the headphones on, lest

I allow the record to just kind of drift

away in the background like some kind of

progressive white noise, and I marvel at

the fact that every time Emerson takes a solo,

which is on every song, his lead line

inexplicably and randomly moves back

and forth between the right and left of the

stereo field, which might be cool, I guesss,

if you were high, and lived in 1974. That

doesn’t occur when he takes a piano solo.

There must have been a belief that a synth

solo must take unfair advantage of the stereo field

in order to be interesting. I’m listening to

the third side before I hear songs I recognize.

“Still. . . You Turn Me On,” followed by “Lucky

Man.” These must have been the tunes that

made it to the radio, likely the band’s bread

and butter in its formative years. They’re very

nice tunes, both, and I might even say that

I enjoyed them, enough even, half way through

this live album experience, to turn the record

over to side four, half of which is just Keith

Emerson improvising like a madman on the piano.

The guy most certainly had chops–and a sense

of humor. I’m forcing down sides five and six.

Skating rink meets science fiction dystopia–I don’t

know what else to make of these concluding

tracks, “Karn Evil 9” in three impressions, whatever

that means, over the two concluding sides

of the album. But this is where that melody comes

from and the title: Welcome back my friends to the

show that never ends. . . which, after a little internet

digging, is not so much the rock and roll

welcome it appears to be, but an ugly greeting

from some futuristic technological warlord.

The good news, though, at the end of

“Karn Evil 9,” impression one, part two, is that

we’re treated to a Carl Palmer drum solo, perhaps

for me, the most enjoyable part of this album.

Would listening to a studio album from ELP,

with it’s heightened fidelity and production

values, be a better experience? Would I like

them more than I do after listening to this?

It might be a worthy experiment,

but an experience that for now

I’m happy not to be searching for.

Notes on the vinyl edition: Welcome Back My Friends To A Show That Never Ends–Ladies and Gentlemen, Emerson Lake and Palmer, Manticore Records, 1974. Three-record set on black vinyl, used but in great condition. The only skip happened during “Lucky Man,” likely the only track the original owner listened to! Might be cleared with a thorough cleaning. This record was sequenced for the stacking turntables that were prevalent at the time, so that you could listen to sides one, two, and three without getting up. You’d then have to turn all three LPs over and re-stack them so that you could listen to sides four, five, and six, again, without getting up. These stackers were automated for convenient continuous listening. A convenience then, now a total pain in the ass, as LP stacking turntables have fallen out of favor–for obvious reasons.

In case you don’t already know: I’m listening to almost everything in my vinyl collection, A to Z, and writing at least one, sometimes two or three long skinny poem-like-things in response for each artist, and on a few occasions, writing a long skinny poem-like-thing in response to more than one artist. As a poet and a student of poetry, I understand that these things look like poems, but they don’t really sound much like poetry, hence, I call them “poem-like-things.” I’ll admit that they’re just long, skinny essays that veer every now and then into the poetic or lyric.