It might be that if I had never read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein that I would have marked this new film by Guillermo del Toro as one of my favorite films in recent memory. However, I have read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, several times in fact, and because I have such a strong and endearing relationship with this early 19th century piece of fiction, I cannot say that Guillermo del Toro’s new film is one of my favorite films in recent memory. I’ve seen interviews with the guy where he claims a similar affinity with the novel, so I was extremely disappointed to find, that while he gets a few things right, he gets a ton of stuff absolutely back-ass-wards wrong. It seems to me that del Toro’s affinity is with the lore, generally speaking, you know, all things Frankenstein, and that he had little concern about making a film that was loyal to its original source material.

Is the film worth seeing? Yes, it is. Is the rest of this review gonna spoil some things for you? Yes, it will. So, if you wanted to see this film and have serious plans to do so, stop reading right now and go watch the film. If you’re curious, and don’t mind spoilers, or, if you’ve seen the film, and perhaps read Mary Shelley’s novel as well, reader, read on.

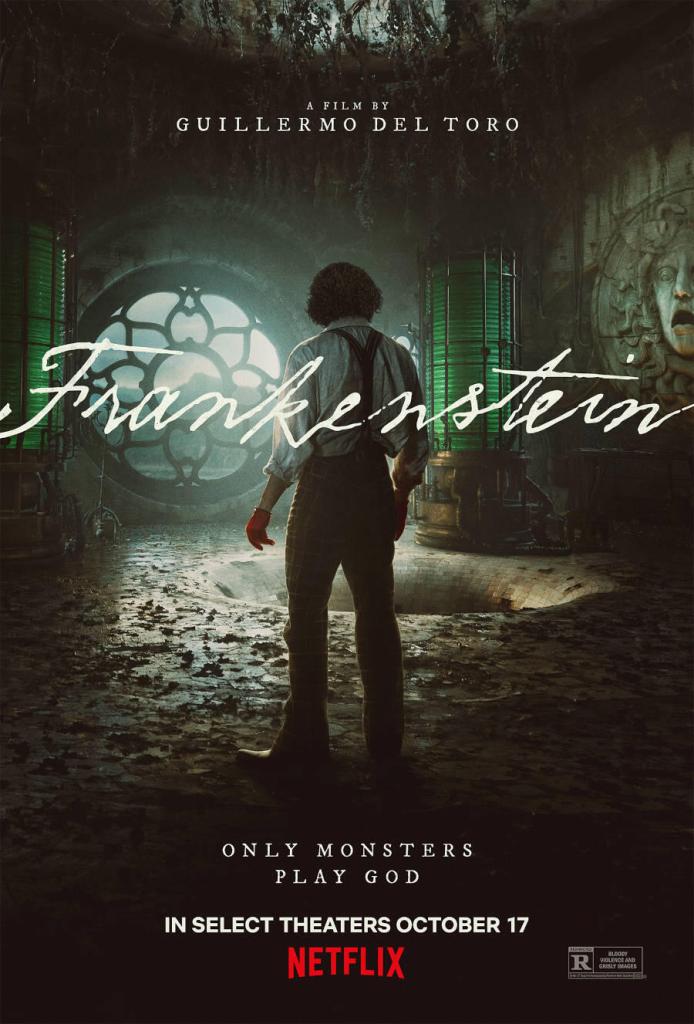

Let’s begin with what the film gets right. Well, it’s a beautiful film to look at it. It’s worth seeing in the theaters as opposed to on Netflix, where you can watch it on your little television or computer right this minute. The visuals are spectacular, appropriately gothic, and the cinematography is lovely. The acting is strong. Mia Goth is wonderful. The monster is wonderful and visually stunning, if not downright beautiful–which I think, emotionally speaking anyway, is appropriate. In Shelley’s novel, that beauty comes through in the language, even though the character knows he’s hideous and everyone else seems to agree. I mean, this monster is clearly disfigured, covered in the imperfections you would expect from a creature assembled from a veritable cornucopia of corpses, but Jacob Elordi is hot, and there’s no disguising that with any number of make-up maneuvers.

The film gets partially right the monster’s visitation on the cottagers–the De Lacey family. In the novel, after his separation from his creator, the creature ends up hiding in a little shack attached to the forest residence of the De Lacey family, an extremely poor but loving group of humans, on which the monster spies over an indeterminate (but long) interval. His spying pays off. From this family, in particular from the tutoring of a little girl by an old blind (uncle? grandfather?), the monster learns vicariously how to speak and how to read. Eventually, when the old man is left alone in the cottage, the monster reveals himself with disastrous results. That much the film gets right. There is much, though, about this bend in the plot line that the film utterly disregards or distorts, including, most egregiously, the manner in which those disastrous results unfold.

Walton’s ship stuck in an ice flow on its way to an exploratory expedition to the North Pole, and Walton as the recipient of the narrative from both Victor Frankenstein and then later from the creature himself, as first the doctor, and then the monster, in the finale of their cross continental chase scene, stumble upon the icebound boat. That’s mostly right, save for a few key details. These are somewhat forgivable changes.

The tone of the film is right, the vibe. Thematically, it’s correct in that, ultimately, we are meant to see Victor Frankenstein as the monster and his creature as sympathetic. But here, and we might as well start with this since I’ve broached the subject, perhaps the film makes Victor too disagreeable and the monster too full of goodness, therefore, glossing over some of the moral nuance in Shelley’s story. The film absolutely skirts the goodness in Frankenstein’s character, especially as a young man, before his obsessions take full control of his faculties. And the creature, while he is the sympathetic one in Shelley’s novel, he also in that same novel does a number of hideous things, is responsible by my count of at least three murders and causes by proxy at least one more death. The film skirts these details as well. The monster does kill in this film, mostly in self-defense as he’s being attacked by Walton’s crew, but the monster in this film does not kill a child, does not murder Victor’s best friend, and does not murder Frankenstein’s beloved bride-to-be. The monster doesn’t murder these individuals–because in Guillermo del Toro’s film, these characters, these MAIN characters from the novel, do not exist! And here’s the thing I found most frustrating about this adaptation: del Toro has futzed with the key plot points and characters in what I find to be unforgivable ways.

I don’t want to get too far into the weeds. I’m not sure that’s the right idiom. I don’t want to do a blow by blow comparison of all the ways in which the plot diverges, or all the ways these film characters are not the same characters from the novel, but let’s just go over the most significant one. In Shelley’s novel, Elizabeth Lavenza, as a child, is adopted by the Frankenstein family as an orphan. As a young adult, Victor falls in love with his adopted sister, eventually proposes to her and they plan to marry. Not technically incest, right? Perhaps del Toro was avoiding even the hint of such a thing. So what does he do? He makes Elizabeth the niece of a character named Harlander, a character that does not exist in Shelley’s novel. On top of this, del Toro makes Elizabeth the betrothed of Victor’s brother William, a few years younger than Victor in the film, while, in the novel, William is a toddler when Victor is an adult! And there’s an entirely added plot element when Harlander, as the chief financier of Victor’s diabolical project, dying of a cancer caused by mercury ingestion, wants Victor to make him a part of the creation in hopes to continue living. What the absolute fuck? Why does that need to be there? Victor refuses to honor his wishes, and in some violent skirmish, sends Harlander to his death down some gigantic hole in his laboratory. And while Victor is kind of hot for Elizabeth, at one point going so far as to try to steal his brother’s girl, she is having none of him, in fact, in a way, other than the monster, of course, she becomes his nemesis in the film, and, dare I say it, falls in love with the creature! The love is unrequited, though, for serious spoiler reasons that I will not reveal here. You’re welcome.

I’ve got other gripes–the historical setting is about a hundred years off, and the final scene between Victor and his monster is inaccurate and saccharine. The historical accuracy is a puzzler, but not a deal breaker, and the closing interaction between “father” and “son” is ultimately forgivable. There are other issues, but I want to bring this little review to a close.

Listen. If you haven’t read Shelley’s Frankenstein, or you have and don’t remember or don’t care about the source material, but you are intrigued by the general gist of this most famous but often misunderstood or misrepresented story, you could do much worse than Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein. For example, you could watch the 1931 version with Boris Karloff. That adaptation sucks in a spectacular way, even though we might be able to credit the film with bringing the concept and image of Frankenstein into our permanent cultural collective consciousness. This is a novel that will not leave us. A quick search for film adaptations of this baby will result in a dizzying array of choices and spin-off after spin-off. But if you would like to see a film that most accurately follows Mary Shelley’s original, the 2004 mini-series, put out astonishingly by the Hallmark people, that’s the best bet for my money.

Sometimes the argument is made that films should not be compared to their source material because they are, after all, a brand new thing, a work unto themselves. The word “adaptation” implies a kind of creative freedom to augment and manipulate and change. That’s fine. For the most part, I understand this and accept it. But when the source material (and this is very particular to the individual) is held dear, or sacred even to some degree, loved in the way that I love Mary Shelley’s novel, it is difficult in the extreme to look past these trespasses. Especially when one, as I have done, has made that source material a significant part of a professional and/or imaginative life.

For further evidence of this last statement, please check out my novel, Monster Talk.